Arapaho

Arapaho-speaking people entered the northern plains probably from west of the Great Lakes before 1700. During the 1700s they ranged from the south fork of Canada's Saskatchewan River south to present Montana, Wyoming, western South Dakota, and eastern Colorado. They obtained horses in the early 1700s, which made hunting efficient. They exchanged horses and other trade items, including products of the hunt, with other tribes. By 1800 the Cheyenne had become middlemen in this trade with the Missouri River villages. The more southerly Arapaho divisions generally stayed west of the Cheyenne to avoid Sioux attacks.

By 1800 the Arapaho were in four divisions from north to south. The Southern Arapaho ranged between the North and South Platte rivers. By 1811 the Arapaho had allied with the Cheyenne and expanded their hunting territory. One Arapaho band had joined Comanches and ranged as far south as present Texas. In the early 1800s Arapahos clashed sporadically with American trappers but also visited the regional trade fairs to obtain goods. By then Arapahos had consolidated into the Gros Ventre division in present Montana, the Northern Arapaho, and the Southern Arapaho.

In 1826, driving the Kiowa and Comanche south, the Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Sioux extended their hunting territory to the Arkansas River. In 1840 the Arapaho made peace with the Kiowa and Comanche and subsequently became their allies. During the first half of the nineteenth century Arapahos sold bison robes at outposts on the Arkansas, South Platte, and North Platte rivers. Those prosperous times ended when American emigrants traversed their region traveling west.

In 1851 the Arapaho signed the Fort Laramie treaty, which guaranteed them use of their range in Colorado west to the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, and east into northwestern Kansas, southwestern Nebraska, and southeastern Wyoming. Southern Arapahos exchanged that territory for a reservation on Colorado's Sand Creek in 1861. Miners and settlers trespassed, which led to the Sand Creek massacre in November 1864 and a war between Arapahos and the United States. A peace treaty was signed in 1865 and a second agreement, the Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867, guaranteed Arapahos a reservation in Kansas. Objecting to the location, they and the Cheyenne accepted a reservation in 1869 in Indian Territory (present Oklahoma) on the Canadian River. Their new reserve was bounded by the 98th Meridian on the east, Texas on the west, the Cherokee Outlet on the north, and the Kiowa-Comanche-Apache Reservation on the south.

During the early 1870s the Arapaho, with a population of about fifteen hundred, continued to live in related family bands and hunt bison. Their agent at Darlington (near present El Reno) occasionally issued goods, and Arapahos returned to the agency in late spring to avoid being attacked by U.S. troops pursuing Cheyenne, Kiowa, and Comanche raiders. After 1876 game was so depleted that Arapahos began relying on wage work and rations from their agent. The band headmen built cattle herds and opened hay fields and communal gardens. In 1886 the agent established Cantonment, Bent's (later Geary), and Seger farming districts and assigned a government farmer to each.

Band, and later district, headmen organized work parties and used their resources to support needy band members. Federal officials acknowledged some of these men (notably Little Raven, Left Hand, Bird Chief, Powder Face, and Big Mouth) as chiefs. Chiefs represented Arapaho interests to the agent. Several times in the 1880s they formed delegations and visited federal officials in Washington, D.C. Trying to persuade the government to abide by the treaties, the chiefs reassured the officials that they were loyal, wanted to learn to farm, and would send their children to school.

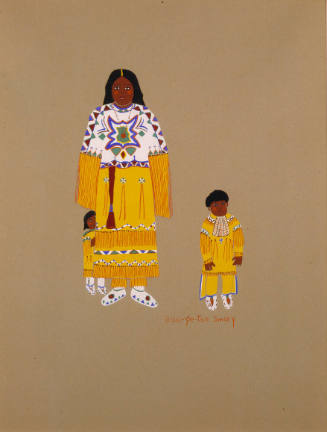

The Arapaho continued to maintain their traditional social organizations and religious observances. Headmen and chiefs were assisted by seven men's societies that were organized by age. Each society had specific age-appropriate duties and was ranked in authority according to age level. A group of seven old men had authority over the societies and all tribal religious ceremonies. There was a comparable group of elderly women with authority in the religious realm.

The most important religious ceremony was the Offerings Lodge or Sun Dance. It was a life-renewal ceremony and an opportunity for individuals to make religious vows to participate in return for supernatural assistance. Arapahos also vowed to donate property or fast for supernatural aid in other contexts. The most important tribal symbol of their bond with the Creator was the Flat Pipe, which the Northern Arapaho kept in Wyoming. The Southern Arapaho had a set of stones symbolizing the pipe. In 1889 the Arapaho embraced the Ghost Dance movement, and shortly thereafter, peyotism was introduced.

By 1889 economic conditions on the reservation had deteriorated. The Cheyenne-Arapaho agent began leasing tribal land to cattlemen. As a result, the Indian herds declined, and malnutrition and other conditions of poverty increased human mortality. In 1891 the federal government sent the Jerome Commission to pressure the Arapaho and Cheyenne to cede land, an agreement that led to further economic decline.

In 1892 each of the 1,144 Arapaho received a 160-acre allotment, and the surplus reservation land was opened to settlers. The government paid the Arapaho and Cheyenne forty cents an acre, far less than the land's value. Pursuant to the agreement, the title to the allotments was held "in trust" so the acreage could not be sold or taxed. The loss of land meant that the tribes would be unable to support themselves as agriculturalists and ranchers. Although settlers preyed upon the Indians, the government ignored the settlers thefts and increased its supervisory powers over the Arapaho and Cheyenne, outlawing, for example, long hair and attendance at ceremonies.

Congress passed the Dead Indian Land Act in 1902, which allowed for the sale of the lands of allottees after they died. In 1906 the Burke Act permitted the government to issue fee patents on allotments so that they could be taxed or sold. By 1928, 68 percent of the allotted Arapaho land had been lost. Families retained a few acres, where they built houses and leased most of the remaining land. Lease money became the main source of income.

Large camps formed annually for religious ceremonies, such as the Sun Dance, and for social dancing during holidays, such as Christmas. People also camped for peyote and Christian church meetings led by Mennonite and Baptist missionaries. Traditions of sharing and gift giving, religious sacrifice, and respect for relatives continued. Successors to the old chiefs tried to protect the land base and persuade the federal government to keep its promises and allow religious freedom.

In 1937 the Cheyenne and Arapaho organized a representative, elective government (known as the Cheyenne-Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma) under the Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act of 1936, in return for guarantees of the trust status of their land and economic assistance. The elected business committee worked on getting title to agency land still held by the federal government, leasing tribal lands, and managing a credit program. Until the mid-1950s, when tribal lands produced oil, the committee operated on a limited budget of lease income. During the 1960s poverty program funds expanded the tribal government's economic role.

Out-migration transformed life in the Arapaho districts because Arapahos joined the military and worked in industry during World War II. The Sun Dance ceased to be held after 1938, so Southern Arapahos began traveling to Wyoming to participate in the Northern Arapaho ceremony. Intertribal powwows replaced the holiday dances. The federal government encouraged Arapahos to move to cities, and gradually those who remained moved out of the rural areas into housing projects begun in the 1960s. Many of the migrants returned and participated in powwows and in reviving chieftainship (which became a ceremonial office) and other traditional activities.

After the Self-Determination Act of 1975 the Cheyenne-Arapaho government grew. The tribes owned bingo parlors, cigarette and sundries stores, and a farm and ranch enterprise, and they received casino profits. Other earnings came from taxes collected on business activity and income from leases on tribal land. The revised tribal constitution of 1975 put the budget under the control of members who attend an annual business meeting. The business committee has eight members.

In 2001 the Southern Arapaho lived within the former reservation boundaries, primarily in and around Canton and Geary in Blaine County, as well as outside that area in Oklahoma, Kansas, Texas, and elsewhere. They numbered about four thousand. In the Canton and Geary vicinity jobs were available through the Cheyenne-Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and the Indian Health Service. Religious ceremonies and powwows remained a focus of Arapaho life.

SEE ALSO: AMERICAN INDIANS, CHEYENNE, SOUTHERN, TERMINATION AND RELOCATION.

BIBLIOGRAPHY: Loretta Fowler, "Arapaho," in Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 13, Book 1, Plains, ed. Raymond DeMallie. (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 2001). Loretta Fowler, Tribal Sovereignty and the Historical Imagination: Cheyenne-Arapaho Politics (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002). Virginia Cole Trenholm, The Arapahoes, Our People (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1970).

Loretta Fowler

© Oklahoma Historical Society

(http://digital.library.okstate.edu/encyclopedia/entries/A/AR002.html)

Person TypeGroup